Ever since I participated in the UKOER programme I have promoted the use of open education and open licensing as a way to increase access to learning and education, so it has always felt natural for me to openly license my own work. The real value of openly licensing a framework like SPaM and releasing it into the wilds of the world wide web is that when you come across someone else using it or writing about it then it’s often a nice surprise and you get a nice warm feeling of satisfaction.

Some people I have worked with are of the opinion that giving my work away with an open license means I won’t get credit for the work, and yes in some ways that’s true, but I’ve never been one for chasing citation numbers and I’d rather not line the coffers of academic journal publishers with my ideas and research, and in fact in most cases people do credit me for the framework, I just don’t necessarily find out about it.

Recently I was using Microsoft Co-pilot to ask it to suggest ways in which the SPaM framework might be used in designing a learning experience for corporate training and development. One of the nice features of co-pilot is that it uses a combination of ChatGPT and Bing to provide links to resources it finds on the web, one of which contained a blog that made reference to SPaM as part of a wider blog about blended learning from the perspective of learning design.

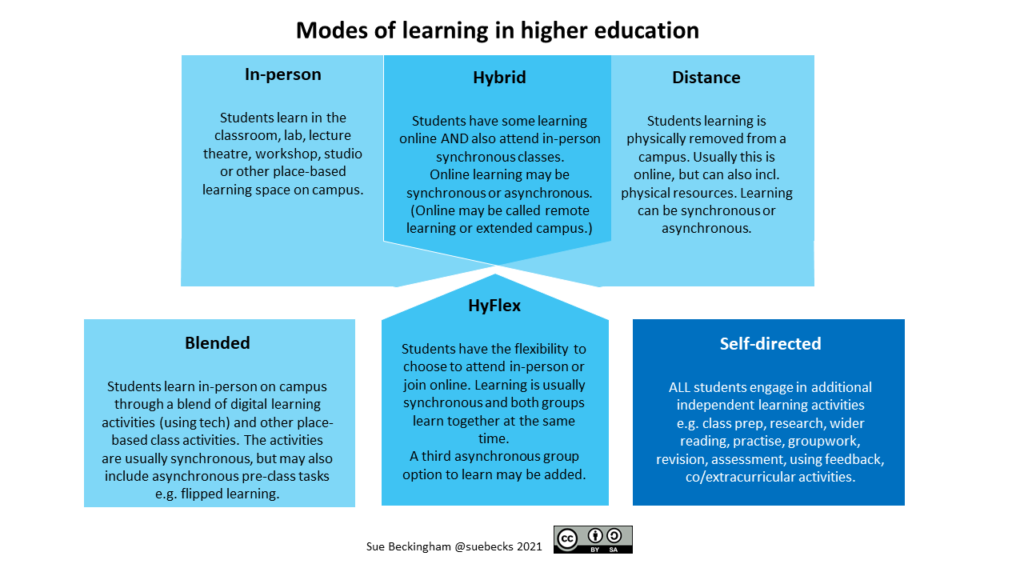

Using Thomson’s framework, the blended learning designer can identify the subject pedagogy to be used, the subject modality and the pedagogy modality. Using these overlapping domains is a powerful and elegantly simple way to view and design flexible learning provision.

Simon Whittemore , 6 October 2023

So, in this case I just happened to come across this post through the very fact I was doing some other work relating to SPaM and I really like the experience of finding out how SPaM is being used and referred to in this ad-hoc manner, much more than I do chasing down citations or h-index value. There’s something wonderfully joyful about just happening upon your work in this way as you navigate the web, knowing that it’s free for others to access and use regardless of their role or circumstance.

So, in 2024 I urge more of you put your work into the public domain under a creative commons license, where you can reasonably do so. It’s not necessarily a route to fame or fortune, but there is something uniquely satisfying about knowing that whilst you retain the copyright to the work, it is free and available to anyone who wishes to make use of it and that when you stumble across others using or talking about it, you’ll get a warm and fuzzy feeling, like you’ve just found a little pot of gold at the end of a rainbow.